Contributing

If you’re reading this, you probably want to contribute to nspyre — great! Any and all support is greatly appreciated. This document lays out guidelines and advice for contributing to this project. If you’re thinking of contributing, please start by reading the immediate info below to get a feel for how contributing to this project works. If you have any questions, feel free to reach out to one of the primary maintainers. nspyre is hosted on GitHub.

Quick Facts

For this project, we use a standard fork & pull model to collaborate, a common practice for open source projects.

We like to run some automated tools to maintain style throughout the repo using pre-commit.

Wherever possible, we use pytest to ensure propery functionality of new code.

Our code generally follows the Google Style Guide, with standard PEP 8 formatting, and some of our own caveats as detailed here.

For documentation, we write in reStructuredText, using Sphinx to generate files and ReadTheDocs for site hosting.

We follow the philosophy of WriteTheDocs – that is, we subscribe to Docs as Code.

To install the tools necessary for development:

$ cd nspyre

$ pip install .[dev]

Or if you use zsh:

$ pip install .\[dev\]

If the above remarks don’t make sense to you, or you simply want a more detailed description of how to do things, continue reading below.

Philosophy

As WriteTheDocs eloquently states,

If people don’t know why your project exists, they won’t use it.If people can’t figure out how to install your code, they won’t use it.If people can’t figure out how to use your code, they won’t use it.

One key to good software development is good documentation. Along with that is the need to strike a balance between efficiency and complexity. Because this is a scientific and an experimentation platform, certain requirements with speed and structure are necessary. We try to keep things as simple and modular as possible, but we are flexible in approach when necessary.

Commit Check-list

Before committing, make sure that all of the pre-commit checks are satisfied:

$ cd nspyre

$ pre-commit run --all

And all of the tests run successfully:

$ cd nspyre/tests

$ pytest

Code Contributions

We understand that for a lot of people using this project, it might be their first time contributing to an open source project. And getting started on any new project can be intimidating, especially for newcomers. So along with information about our workflow in this project, our style guides, and particular information on how to get involved, we’ve included some basic information, collated from various sources on a number of important topics. We hope this helps you on your journey. (If you are already a pro, we’re happy to have you – you can skip to our style guide here.)

Version Control

First thing’s first — Git. Git is an example of a distributed version control system (DVCS) commonly used for open source and commercial software development. A version control system (VCS) tracks the history of changes as people and teams collaborate on projects together. As the project evolves, teams can run tests, fix bugs, and contribute new code with the confidence that any version can be recovered at any time. Developers can review project history to find out:

Which changes were made?

Who made the changes?

When were the changes made?

Why were changes needed?

Git grew out of the needs of the developers of the Linux kernel and is one of the most widely-used VCS tools available. GitHub is a Git hosting repository that builds collaboration directly into the development process by providing developers with tools to ship better code through command line features, issues (threaded discussions), pull requests, code review, and more. If all this information is new, then please read this: Understanding the GitHub flow — it’s a 5 minute read and it will make your life a lot easier going forward. (If you want a much deeper explanation and a good reference source to get up to speed on the basics of using Git and GitHub, go to the Git Handbook.)

Testing

We use pytest to run tests on nspyre. Proper testing insures that when you make a code change, nspyre still works as advertised. Run pytest and ensure all tests pass before making any commits:

$ cd nspyre/tests

$ pytest

==================================== test session starts =====================================

platform linux -- Python 3.9.6, pytest-6.2.4, py-1.10.0, pluggy-0.13.1

rootdir: /home/xx/yy, configfile: pytest.ini

collected 10 items

...

===================================== 100 passed in x.xxs =====================================

If you are writing any new nspyre functionality, make sure to write test cases to ensure your code will be tested!

Pre-commit

In order to ensure consistent style throughout nspyre, several automated tools can be run automatically by git when attempting to commit. To enable these pre-commit hooks:

$ pre-commit install

Then, when creating a commit, the checks will be run:

$ git commit -m "a descriptive commit message"

Check for added large files..............................................Passed

Check docstring is first.................................................Passed

Check that executables have shebangs.....................................Passed

Check for merge conflicts................................................Passed

Check that scripts with shebangs are executable..........................Passed

Check Yaml...........................................(no files to check)Skipped

Fix End of Files.........................................................Passed

black....................................................................Passed

flake8...................................................................Passed

mypy.....................................................................Passed

If any checks fail, be sure to fix the issues. If you want to run the checks

without actually committing, simply pre-commit run. To force it to run on

all files, pre-commit run --all. All packages used for pre-commit checks can be

updated by running pre-commit autoupdate.

Forking & Pull Requests

Great, now that you understand the why and how of Git, GitHub, code testing, and style compliance, let’s explain the workflow to contribute. We use the fork & pull model to collaborate. This means that to contribute to the project, you first need to Fork the project on GitHub. A GitHub fork is just a copy of a repository (repo). When you fork a repo, you are storing a copy of that repo on your personal account. Doing so grants you full write access to edit files and develop the code on your version of it. After making changes to the codebase – squashing bugs, adding features, writing docs – make a Pull Request. When you git pull on a codebase, that’s the git term for pulling updated and/or new files from one version of a repo to another; you are simply updating files in a particular direction. Thus, pulling applies in many different contexts (more info below). A pull request, therefore, is a request you make for the maintainers, of the original repo you forked, to review & merge your edits into their version of the code stored on their repo (you can, of course, make pull requests on your own repositories).

To make things concrete, let’s actually perform this using the command line.

First you need to fork the repository of interest. To do so, click the Fork button in the header of the repository.

When it’s finished, you’ll be taken to your copy of the nspyre repository, which will be located at https://github.com/[your-username]/nspyre. The rest can now be completed using the console:

# navigate to the directory you want to store your local copy of the repo

$ cd ~/SourceCode

# download the repository on GitHub.com to your machine

$ git clone https://github.com/[your-username]/nspyre.git

# change into the nspyre directory that was created for you

$ cd nspyre

# create a new branch to store any new changes

$ git branch descriptive-branch-title

# switch to that branch (line of development)

$ git checkout descriptive-branch-title

# make changes, for example, edit contributors.md and create my-spyrelet.py

# stage the changed files

$ git add contributors.md my-spyrelet.py

# take a snapshot of the staging area (anything that has been added)

# the -m flag adds a comment to the commmit

$ git commit -m "my snapshot"

# push changes to github

$ git push --set-upstream origin descriptive-branch-title

You will notice the addition of two new terms – branch and push. Each repository can have multiple versions of its codebase that are under development. The main branch is the main version of the code on the repository and is the root branch from which all others originate. This is the official working version that is used out in the wild and the one you eventually want your changes to appear on. When forking a repo, you also get all the different branches at the time of copying. When contributing on an issue, you first want to search existing branches to check if someone has already started a branch for work on that issue. If not, start a new one and make sure to give it a descriptive title so people easily understand what’s being worked on (e.g. refactoring-pep8, awg-spyrelet, driver-gui-bug, etc). Then you need to checkout the branch to which you want to make changes, making sure to add and commit them so they are reflected locally.

Finally, the push command updates files from one location to another, but in the opposite direction as pull. git pull brings any changes from the target repo on the servers and updates them into the version/branch that you currently have checked out on your local copy. git push does the opposite. It takes any changes on your local copy of the branch you have checked out and reflects those changes on the repository. If you don’t git push your commits then they will not be uploaded to the repo; this also means they won’t be backed up. So it’s good practice to push your progress at least daily so it is uploaded to the repository.

Note

You can pull a branch you are working on from the github repo to get the most up-to-date copy locally, pull one branch into another to transfer certain commits between them, or pull in the reverse direction to bring your updates into the main repo (i.e. push from your local console).

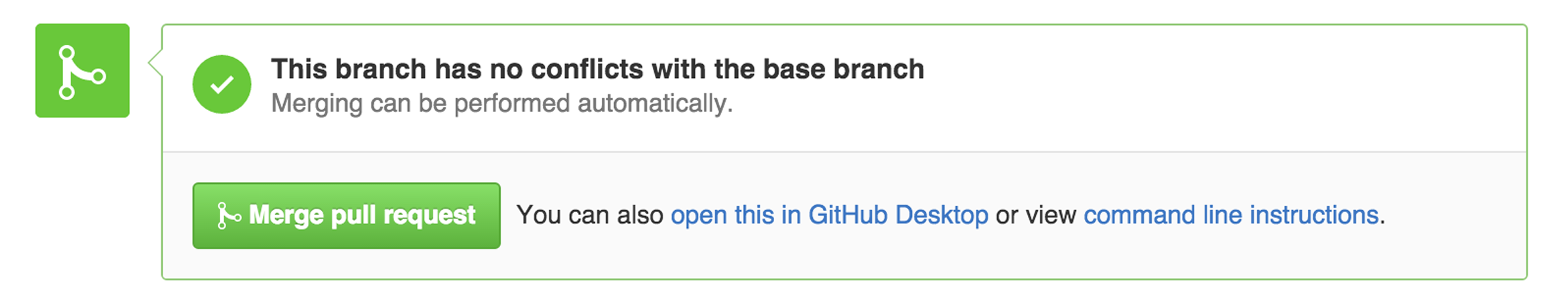

Creating a Pull Request

Once you’ve vetted your code for errors, checked to make sure you’ve followed all the project guidelines – and, most importantly, documented your code – it’s time to make a pull request.

In the main repository you want to merge into, either click the Pull Request tab, then from the Pull Request page, click the green New pull request button, or, navigate to the branch (to which you made edits) in the drop-down box on the repository homepage, and click the green Compare & pull request button. Then, look over your changes in the diffs on the Compare page, make sure they’re what you want to submit. Give your pull request a title and write a brief description of your changes. When you’re satisfied, click the big green Create pull request button. Congrats, you’ve submitted your first contribution ready for merging!

All that’s left is to officially merge your changes into main and delete the development branch you were working off of, if the associated issues have been closed and the branch is no longer needed. This is something the maintainers of the project will do once it’s been confirmed that all the project guidelines have been followed and, in particular, checking your code works!

(For more detailed information on creating a pull request from a fork, see here.)

Virtual Enivronments

Note

Make sure you have some sort of virtual environment implemented in your workflow. The environment management tools built into Anaconda are great if you are already using Anaconda for your scientific packages. If you are just using pip, then check out venv – it has a lot of improvements over virtualenv and is the preferred way for Python 3.3 or newer, which is why it’s now included by default.

Development tools

Tip

The above steps for forking a repo and making a pull request were performed on the command line. In addition to performing these steps directly on GitHub.com, many popular text editors and IDEs have integrated tools for using git/github directly within their environments. (PyCharm, Sublime Text, and VS Code are a few favorites)

Perform

git checkoutandgit branchin one command:# check out an existing branch: $ git checkout <branch> # create a new branch: $ git branch <branchname> [<start point>] # create a new branch and check it out in one command: $ git checkout -b <newbranch> [<start point>]

Code Style

The nspyre codebase generally follows the Google Style Guide for both code and docstrings. Black, Flake8, and MyPy are used to enforce style compliance.

Type hints according to PEP 484 are encouraged. Type hints are the annotations that indicate the type of arguments and the return value of a function. Unlike a static programming language, Python neither requires these type declarations nor does it use them to do runtime type checking. The benefit to putting this information outside the docstrings is to increase their readability, while also making both static analysis and refactoring easier.

All functions, methods, and classes are to contain docstrings. Object data model methods (e.g. __repr__) are typically the exception to this rule.

def function_with_pep484_type_annotations(param1: int, param2: str) -> bool:

"""Example function with PEP 484 type annotations.

Args:

param1: The first parameter.

param2: The second parameter.

Returns:

The return value. True for success, False otherwise.

Raises:

ValueError: An argument was invalid.

"""

Documentation Contributions

Documentation Style

When contributing documentation, please do your best to follow the style of the documentation files. This means a semi-formal, yet friendly and approachable prose style. Tutorial type information should be placed in the getting started sections. If you are writing documentation for a major spyrelet, create a new .rst file and make sure to add it to the appropriate toctree in index.rst.

Guidelines:

When presenting Python code, use single-quoted strings (

'hello'instead of"hello"); this applies to code as well!Make sure to show examples of code output and expected results. The use of screenshots for GUI elements is acceptable, but make sure the resolution is high enough.

Refer to the .rst file for this section as a reference for good format styling.

Don’t go more than three levels of headings deep; a maximum of two levels is encouraged.

Writing Docs

Documentation improvements are always welcome! The documentation files live in the docs/ directory of the codebase. They’re written in reStructuredText, and use Sphinx to generate the full suite of documentation, with site hosting provided by ReadTheDocs. Writing documentation is a great way to start contributing, especially if you are new, and will help get you familiar with the codebase.

reStructuredText is an easy-to-read plaintext markup syntax and parser system. Markdown is another, slightly simpler alternative. reStructuredText is a bit harder to use, but is more powerful and is widely used for Python documentation.

The reasons for using a markup language are straight-forward:

easy to write and maintain (strong semantic markup tools and well-defined markup standards)

still makes sense as plain text (easily legible in raw form)

renders nicely into HTML (this looks nice, doesn’t it?)

Building

To build the documentation locally, navigate to docs and run:

$ make html

or, skipping some non-essential steps:

$ make fast

You can then view it by opening the root html file docs/build/html/index.html

with a web browser.

reStructuredText

There are many resources on reST syntax, but we’ve found it helpful to know these basic things when starting out (and as a quick refresher!).

Paragraphs in reStructuredText are blocks of text separated by at least one blank line. All lines in the paragraph must be indented by the same amount.

Indentation is important and mixing spaces and tabs causes problems. So like Python, it’s best to just use spaces. And typically, you want to use three spaces. Yes, you read that correctly, we’ll explain why in a minute. (A standard tab is equivalent to four spaces.)

Inline markup for font styles is similar to MarkDown:

Use one asterisk (

*text*) for italics.Use two asterisks (

**text**) for bolding.Use two backticks (

``text``) forcode samples.Use an underscore (

references_) for references.Use one backtick (

`references with whitespace`_) for references with whitespace.Links to external sites contain the link text and a bracketed URL in backticks, followed by an underscore:

Link to Write the Docs <https://www.writethedocs.org/>`_.To support cross-referencing to arbitrary locations in any document, the standard reST labels are used. References point to labels. For this to work, label names must be unique throughout the entire documentation. There are two ways in which you can refer to labels:

If you place a label directly before a section title, you can reference to it with

:ref:`label-name`. For example:.. _my-reference-label: Section to cross-reference -------------------------- This is the text of the section. It refers to the section itself, see :ref:`my-reference-label`.

The

:ref:role would then generate a link to the section, with the link title being “Section to cross-reference”. This works just as well when the section and reference are in different source files. Note that labels must start with an underscore, but it’s reference does not; additionally, label definitions start with two periods and end with a colon.Labels that aren’t placed before a section title can still be referenced, but you must give the link an explicit title, using this syntax:

:ref:`Link title <label-name>`.

If asterisks * or backquotes \ appear in running text and could be confused with inline markup delimiters, they have to be escaped with a backslash:

*escape* \* or \\ with "\\"yields escape * or \ with “\”.

Headers

Section Headers are demarcated by underlining (or over- and underlining) the section title using non-alphanumeric characters like dashes, equal signs, or tildes. The row of non-alphanumeric characters must be at least as long as the header text. Use the same character for headers at the same level. The following creates a header:

=========

Chapter 1 while this creates a header at a different level in the doc: Section 1.1

========= -----------

A lone top-level section is lifted up to be the document’s title. If you use the same non-alphanumeric character for underline-only, and underline-and-overline headers, they will be considered to be at different levels. Any non-alphanumeric character can be used, but the Python convention – which is to be used – is as follows:

#with overline, for parts

*with overline, for chapters

=, for sections

-, for subsections

^, for subsubsections

", for paragraphs

Lists

For enumerated lists, use a number or letter followed by a period, or followed by a right-bracket, or surrounded by brackets. You can also use the # symbol for an auto-numbered list:

1. Use this to format the items in your list like 1., 2., etc.

A. Use this to make items in your list appear as A., B., etc.

Both uppercase and lowercase letters are acceptable.

I. Roman numerals are also acceptable -- both upper- and lowercase.

(1) Numbers in brackets are also acceptable.

3) So are numbers followed by a bracket, and you don't have to start numbering at one either.

#. A numbered listed useful for re-arranging items frequently.

For bulleted lists, use indentation to indicate the level of nesting of a

bullet point. You can use -, +, or * as a bullet point character:

* Bullet point

- nested bullet point

+ even more nested bullet point

Code Samples

There are many different ways of using reST to display code samples, – or

any text that should not be formatted – but we explicity use the

code-block directive for simplicity. Here’s an example:

This is the paragraph preceding the code sample:

.. code-block:: python

#some sample code

print('Hello, World!')

There is one exception to the rule: when you want to display an interactive

session. Doctest blocks are text blocks which begin with “>>>”, the Python

interactive interpreter main prompt, and end with a blank line (an unused prompt

is not allowed - it will break things). Doctest blocks are treated as a special

case of literal blocks, without requiring the literal block syntax. If both

are present, the literal block syntax takes priority over Doctest block syntax:

This is an ordinary paragraph.

>>> print 'this is a Doctest block'

this is a Doctest block

A Final Word

You may have noticed that the directives in the above examples all use a similar

markup syntax – that is, they start with .. [name]. Explicit markup is

used in reST for most constructs. There is also a secondary idea called a directive

- a generic block of explicit markup. It is one of the extension mechanisms of

reST, and Sphinx makes heavy use of it. A directive ends it’s generic block with

:: after it’s name (e.g. .. code-block:: shown above). This syntax is used

extensively for more complex features, such as images, roles, comments, and admonitions.

Again, there is a lot that can be said about markup languages; we haven’t even talked about tables, roles, field lists, or substitutions. But included here is everything you need to get started and all of the information necessary to write this very Contributing section of the documentation. Lastly, there are many resources already available online and you should avail yourself of them:

Resources

There’s a lot of online resources available covering every imaginable aspect of software development. Below is a collection of the most useful as they pertain to development in this project; they were referenced heavily in the construct of the above material. Hopefully, they are just as useful to you too.